On the final day of the conference, the spotlight was on the power of platforms in relation to businesses. If a business does not appear in Google’s search results, does it exist?

The WORK2019 conference culminated on Friday in the closing seminar of the SWiPE consortium (Smart Work in Platform Economy), which is funded by the Strategic Research Council at the Academy of Finland. Launched in 2016, the project studied the transformation of work and entrepreneurship in the platform economy era.

I appear on Google, therefore I am

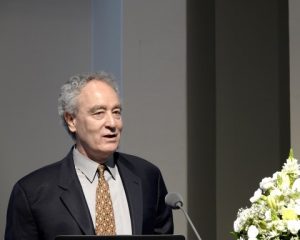

Friday featured a keynote speech by Professor Martin Kenney from the University of California. His speech was titled Platform-Dependent Entrepreneurs and Business: Understanding Power in the Platform Economy.

Digital platforms are an increasingly important part of the global economy, and businesses are more and more dependent on them. According to Kenney, small businesses and entrepreneurs in particular are at the mercy of platforms – for better or worse. Consumers turn to Google for information about products and services, so staying at the top of search results is vital for small businesses.

“Does a business exist if it cannot be found on Google? How about a restaurant, if it is not on Google Maps? The answer is no,” Kenney stated.

The value of platform businesses has exploded. In March 2019, seven of the world’s most valuable businesses were platform businesses. There was only one platform business on the list in 2002. The success of platforms is partially due to their ability to expand into several industries. For example, Amazon’s operations now include logistics, streaming and cloud services in addition to e-commerce.

Platforms provide market access for many businesses. People selling their products on Amazon and Etsy often receive support and training for operating on the platforms. Google, in turn, makes people aware of businesses.

However, platforms have a disproportionate amount of power over entrepreneurs. The platforms can see all the content that is put on them. If a product is selling particularly well, an e-commerce platform may start to sell a similar product itself. Platforms can change their terms of use unexpectedly and, for example, increase the share of their own reward. Platforms also manage the rating and referral systems based on which users choose the products and services they use. Kenney gave a chilling example of this.

“Do you think that hotel ratings on Booking, for instance, come from people’s reviews? In reality, they are influenced by whether the hotel pays for advertising on the platform.”

Many platform-dependent entrepreneurs have sought to tackle these problems by generating revenue from multiple sources. Since Google takes 45 percent of Youtube’s advertising revenue for itself, YouTube content creators have started to acquire sponsors themselves. Über drivers around the world have gone on strike for better working conditions and wages.

“The balance of power between platforms and platform-dependent entrepreneurs is dramatically out of whack, but there are possibilities to redress this balance,” Kenney remarked.

Attention should be shifted from platforms to the entrepreneurs who depend on them. For example, Kenney believes that a change in teaching is already noticeable in business schools.

“Finally people are becoming aware that where there are a few platforms, there are millions of small businesses.”

We have to look after the wellbeing of platform workers

SWiPE’s closing seminar also included a panel discussion titled Digital Work in the Platform Economy, where some of the findings of the three-year research project were presented.

The speakers were Professor Anne Kovalainen from the University of Turku, leader of the SWiPE consortium and the WORK2019 conference, Adjunct Professor Seppo Poutanen, leader of the consortium’s subproject at the University of Turku, Research Director Petri Rouvinen from Avance Attorneys, leader of the ETLA subproject and Adjunct Professor Laura Seppänen, leader of the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health subproject.

A book created in the project and published by Routledge, Digital Work and the Platform Economy: Understanding Tasks, Skills and Capabilities in the New Era, was at the centre of the discussion. The book has been edited by Seppo Poutanen, Anne Kovalainen and Petri Rouvinen, and will be published during 2019 or 2020.

Anne Kovalainen opened the panel discussion by looking back at the starting point from which the SWiPE research project began in 2016. The platform economy was quite a new topic at the time.

“At the beginning of the project, there wasn’t a clear picture of what platform work really meant. We wanted to know who in Finland works on platforms and how platforms affect work,” she said.

Among other things, the book explores the effects of the platform economy on workers’ health and wellbeing. A typical situation in platform work is that there is either too much or too little work. Job insecurity and a high workload can be manifested as workers becoming ill, for instance.

“Platform workers need support especially in terms of healthcare,” Seppo Poutanen pointed out.

In her speech, Laura Seppänen emphasised the humane side of digital work. According to a study conducted by the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, the ability of employees to be proactive at work prevents health risks.

“For example, the working conditions of food couriers in terms of proactiveness are limited, but if necessary they have the resources to organise and collectively resist changes in management structures,” Seppänen said.

It seems clear that the platform economy is here to stay. However, its significance cannot be discerned by simply looking at numbers. Research Director Petri Rouvinen pointed out that although platform work accounts for only one percent of all work done in Finland, the impact of platforms on the labour market is far greater.

“Platforms restructure industries and impact work. For example, with Google and Facebook, the role of newspapers and magazines as information sources and advertisers is changing.”

It is important to study how platform work interacts with so-called ordinary work in the longer term. Many of the speakers at the conference warned about the power of platforms and problems related to them, but they also enable many good things. Platforms have made our lives easier in many ways and created new job opportunities. Rouvinen believes we should find a balance between the positive and negative effects.

“How can we get the power related to taxation and regulation back from the platforms to society without removing the platforms’ positive effects?” Rouvinen asked.

Text: Kira Keini / Kaskas Media

Images: Eija Vuorio / WORK2019 organising committee

The WORK2019 conference is an international forum held between 14.–16.8.2019, where research knowledge and experiences about work are exchanged among researchers and experts in work and the fields of working life. The conference is organised by the University of Turku together with the Turku Centre for Labour Studies TCLS, the SWiPE consortium funded by the Strategic Research Council at the Academy of Finland, and the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health.